Zak Smith is known for his collection of illustrations inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (one illustration for every page), his series 100 Girls and 100 Octopuses, and his memoir We Did Porn, about his time working in alt-porn. His art tends to be hysterically convoluted and intricate; he paints beautiful women (sometimes nudes, other times sexually explicit); his colors are bold and figures exist on a sliding scale between highbrow illustration and synthetic realism.

I met up with Zak Smith at a restaurant in downtown Chicago in the winter of 2012. He was having lunch with a small group of MFA students from School of Art Institute of Chicago, who had brought him to Chicago as a guest lecturer. Needless to say, it wasn’t difficult to find them among the typical Loop lunch crowd. They welcomed me to their table, bought me lunch, and let me eavesdrop on their conversations regarding Smith’s time as a graduate student at Yale, his work, and personal life. Smith seemed at home with them and responded to their questions with his unique blend of intelligence, self-effacing humor, and honesty. At a certain point, I jumped in and we had the following conversation.

Jacob Singer: How would you describe your subject matter and style?

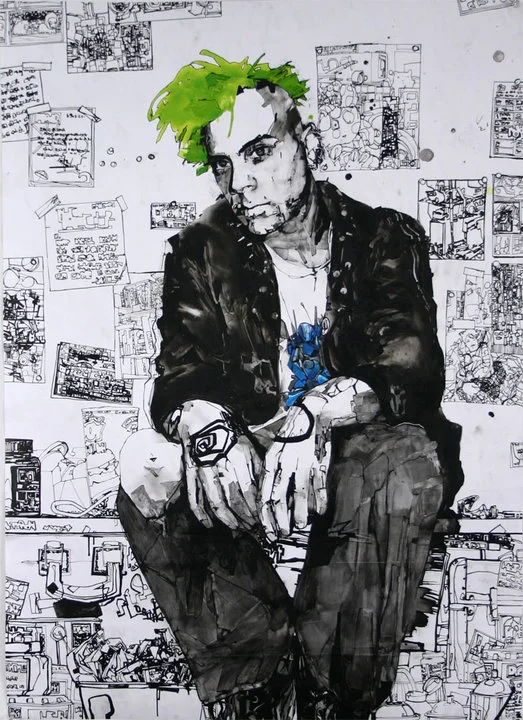

Zak Smith: I never like that question because you have the art right there. Presumably this interview will be published next to some pictures. I don’t like the process of describing things, which can be boring, but if I had to describe it, which I do once in a while, I would say that they’re dense, labor intensive, and intricate. They’re busy and they seem itchy; it’s like they’re trying to get off the page. It’s like there is this little vibrating thing in all my pictures. It’s not on purpose. It just happens. It’s got this caffeinated look.

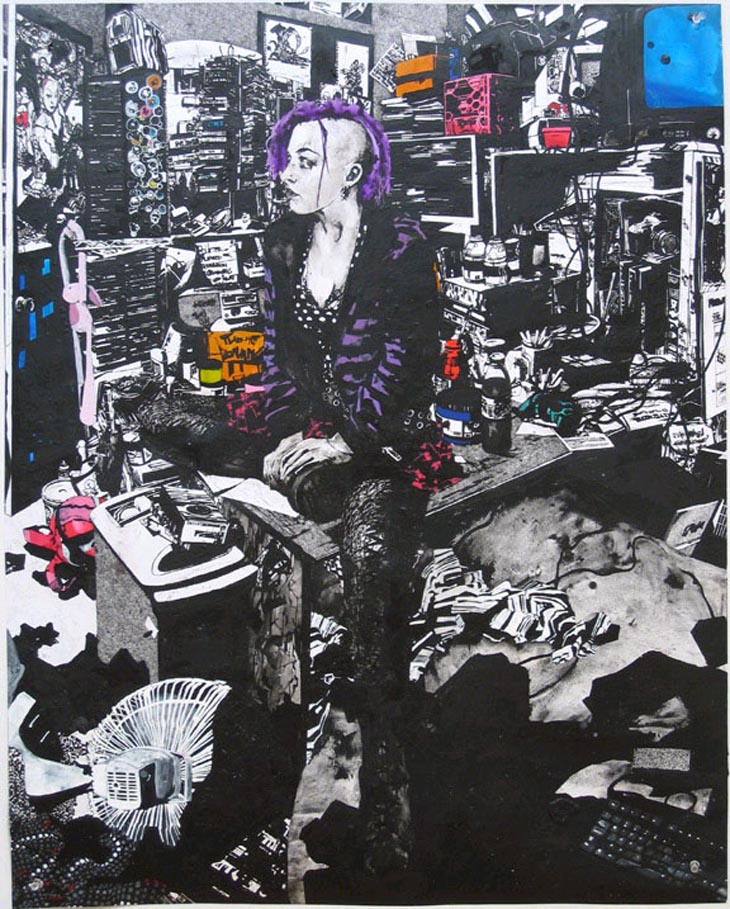

JS: It seems that you’re actively participating in two traditional painting genres: female nudes and still life. But you mash them together in an interesting way. There will be the female nude as the center of the canvas, but she is surrounded by all this stuff.

ZS: I think part of it is that in other art and media I hardly see anything that looks real. It doesn’t look lifelike. The people look off. Their apartments look empty. How many times have you seen a movie where the office is empty, nobody has anything taped to their wall? Like in that movie Drive, which is a fun movie, but he goes into this strip club and it’s the cleanest strip club I’ve ever seen. It creates a barrier where things don’t feel real – at least to me. So I seize details that feel real, which make things look like real life. Open a purse and inside it you will find a change purse with a crab on it, keys, gun, and whatever else. Wong Kar-wai and Wes Anderson seem to catch that on some level. Some people say that my pieces are messy. I’m always like, “I don’t believe you.” If you have kids your house is messy, and if you are a guy you definitely have a messy house. Right now we are at a restaurant and it’s a cluttered place. It’s a nice, clean restaurant but this table is just chaos. There’s a milk container, a pepper shaker, a PBR can, empty sugar packs, and silverware everywhere. You never see this in art or media

JS: So how do go about assembling some sense of order from all the chaos? Do you sketch out a piece before you begin painting or do you revise on the canvas?

ZS: On the portraits, I start with the head because it’s technically the most difficult. I have to really concentrate. So when I get done with that the rest of the painting has to do with the size and scale of the face and body. I mostly do it right there on the paper. Every once in a while I will step back and do sketches, but it won’t tell you that much because sketches don’t tell me how it will look when the paint hits the paper. It’s weird. Color isn’t predictable. I’ll put down the color, and if it doesn’t work, I white it out and start again. Sometimes they look very finished, like they were all planned out in advanced. With regards to pictures that aren’t the portraits, sometimes I have a clearer idea when I start but usually end up changing it about halfway through. What amounts to a good picture is ultimately more than what you can hold in your brain. It’s like if you have a real good idea for a song or a movie – that only gets you so far. You actually have to do it and that’s when you add in all sorts of details. With writing, it’s the words and the phrases that make it great; the idea can only get you so far. I don’t trust that planning in advance will make it great.

JS: What’s your workspace like? Is it cluttered?

ZS: I don’t have a separate studio. I feel that everyone who has a separate studio is always going, “I should get into the studio this week.” I wake up and my art is right there and it’s not finished and it looks terrible. So I’m like, “I’d better get on that.” My table is in the corner of the living room. Basically anyone who walks into our house walks right past my desk. And that’s nice because my work is very involuted. It requires a lot of concentration so it’s nice to have other people ambiently there so I don’t have to make an effort. I have a few walls and stick everything on the wall so I don’t have to look in the drawer. There are a ton of notes and scraps everywhere like tools ready to be used. I don’t have to think about where it is – it’s there, whether a picture or something I am working on for Artillery or the blog.

JS: You seem like a bit of a workaholic: art school, Yale MFA, galleries, books, and your memoir about working in alt-porn. Can you talk about your notions of work and education?

ZS: Art school gets you used to the idea of art being your job and that you don’t do anything else. If you’re not making art, you’re not working. If you can’t do that you really need to get out. It’s terrible if you don’t end up being an artist after art school, because then you don’t have anything.

At Cooper Union you were going to make art all day and be judged on how well you made it, but mostly how much art you made. You have five classes, so you make five classes’ worth of art. You learn how to schedule time to make art. While practice doesn’t make you perfect, it does make you more you.

Back then I was known as the guy who was always multidisciplinary: photo, sculpture, drawings. I was doing experimental photography at Union, but in graduate school I discovered that it was really fun to invent a technique that makes painting look like those experimental photos, which is funny now because many people don’t think my paintings are paintings. Having spent so much time looking at those experimental photos, I know how the grain moves across the photo. If I sit and draw something, it doesn’t look like a drawing you typically see in charcoal with shading lines. If I draw something it will look more photographic; it’s part of how I render the material.

JS: How do you take advantage of that flattening effect of photography?

ZS: There are different realisms. Basically when you take a three-dimensional object and make it into a two-dimensional object you have to sacrifice something, otherwise you’re not emphasizing anything. You’ve got to pick your poison deliberately in order to transfer the image in a certain way – texture, light, color – but you can’t do everything. You’re always sacrificing something. Jan van Eyck sacrifices a certain amount of movement. Certain contemporary photorealists sacrifice focus. The point is that there is more than one realism. It’s essentially a translation. What I do in my paintings a lot is like take different translations or different realisms and stick them next to each other and seeing what that looks like.

JS: I’m interested in your sense of realism. I have always associated you with hysterical realists like Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace. Some critics have accused them of spending too much time on details. As you just said, they seem to be making different realisms. They’re creating deeply textured alternate universes.

ZS: It’s what they naturally emphasize and de-emphasize that makes style and that style creates a world. What do people notice? Different people notice different things about the world. There is this passage in a Vonnegut book about this practice where one tribesman is responsible to know a family’s entire history. That person experiences the present moment deeper than everyone else because everything he sees reminds him of something else that had previously happened. He can make connections – like Wallace, who might take something banal and make it interesting by tying in all these connections between characters, plot, and theme. All the connections he’s making give it meaning.

JS: Let’s talk about your painting, “Mara.” In the background there is a Jimi Hendrix poster with illegible font. It’s a popular image of Hendrix. You have a jacket hanging on the wall near what looks like cassettes. The background is recognizable but distorted.

ZS: That’s my room in college. I’m interested in the sharpness and specificity of the way shapes move, but I don’t always care about making those images look real. It’s interesting to me to create abstractions using techniques that realism uses. Anyone who works in computer programming or graphics knows that you create a lot of programs that make abstract things look real by a certain proportion of shade, distance, crumble, color, degradation, dark, and light. Then it looks real although it has no antecedent.

JS: I have always really liked how the smoothness of your human figures gives way to harder geometric patterns. It reminds me of Gustav Klimt. Can you talk about your influences? Who did you go to as resources?

ZS: Klimt was always interesting to me, and I always thought that his worst work was his most popular. “The Kiss” is a terrible painting. It’s just not interesting at all. “Hostile Powers” is a wonderful image. I imagine Picasso and Klimt working at the same time. Klimt was moving into abstraction in a much more interesting way. His color was light years ahead of anyone else. There is something mannered about his figures, something theatrical that kept people from thinking highly of him. He was a much better painter than he is created for. People like him, but he is a much better painter than many of his avant-garde peers and was a much more abstract painter. He’s very postmodern in the sense that he got different kinds of things on the surface at the same time. In terms of the surface of the actual paintings I never really liked how he got paint there but the drawing and the choices are really wonderful.

JS: Can you talk about the coloring and texture of your series I’m Really Busy and Stuff?

ZS: This series started when I moved back to New York after grad school. It was just an experiment. I had a chart where I wrote down a series of ideas that interested me on an x-and-y axis and tried to draw a picture of that idea. I just kept the ones that worked. It’s just boring art school stuff. I was trying not to let the idea do the work for me, and ask myself: can I make this dumb idea so well that it’s new and different? I drew them out of thin air, colored them, and then took the drawing and used it as a photographic negative – which is impossible to describe because nobody’s had this experience in a darkroom. There’s no photography involved. It’s just this method of printing that I invented, like Man Ray. Contact printings have an interesting fade to them. Eight Variations is the same technique. People don’t understand them. They think they’re either photographs or computer generated. Basically, if you look at a rayograph or a rayogram, if instead of using an object you used a drawing and the light goes through the drawing and makes these sort of strange textures.

JS: Are you playing with narrative? Obviously images don’t have time but they’re part of a series. Are you toying with movement through time or interconnectedness?

ZS: It’s something like that but it doesn’t have a name. We’re used to the idea of narrative in the context of art because when we see a picture in real life, for any reason, it’s attached to a story, because they are used in traffic signs, news, and advertising to tell us information. If you look at a picture and what you primarily see is the story then the picture sucks. Pictures should look good. Any asshole can tell a story.

But there is something else, which is just looking at things for a long time for something that is internal to the piece of art, abstract or otherwise. We don’t have a name for it, but it exists. It doesn’t unfold in time. It’s more like a sandbox than a story. Instead of event one, two, three, there are a million events, like pieces of sand, all existing at the same time and in the same place. Where do you start? It’s like Disney World. You don’t go in a certain order. You pick and experience parts of it. It’s like tourism in a certain sense.

JS: Tell me about creating an illustration for each page of Gravity’s Rainbow.

ZS: I did it all in 2004. My original idea was that I would do it over the course of a couple years and that it would be really easy. I would just build them up slowly. The drawings are small. I would do one or two a day and then do other stuff – it wouldn’t take long. I liked Pynchon and all his ideas were in my head and I kind of wanted them out. I just started and then a curator saw what I had and asked if I could have them ready in two months. So I had to kick it into high gear.

JS: How big are they?

ZS: Everything in the book is actual size. I never knew it was going to be a book. I wanted them to be sketch size, I wanted it to go straight from my brain to the page, I wanted to do that quickly. That is what’s great about sketches. You have this thought and you make the image quickly. It’s immediate and not over thought. There isn’t a lot of rumination or things getting in the way. See a sentence, think of an image, and make an image as quickly as possible.

JS: What’s it like looking at them now?

ZS: There are so many pictures. Some I look back and think are terrible and others are like, “Wow, look at that.” It’s a strange position to be with your own work. I guess when you do over seven hundred pictures you become objective with your own work. There are so many I would like to redo, but on the other hand it was a great learning process in that my art has always been influenced illustration but it isn’t illustration. That didn’t mean much to me at the beginning, but now I realize that there are important but subtle differences in how you approach a picture that you see in comparison to something you see that comes with something. In professional illustration you develop techniques around communicating very specific ideas. In fine art you develop techniques for expressing whatever you want, including things you thought while making the picture in the first place. The skill sets and techniques required to do both overlap, but are slightly different. So in this project I had to refine what I did to match the format. For example, if I was drawing the riot scene in the book in an illustration I would emphasize getting a sense of movement, but in a picture to be looked at for a long time in a gallery, I would emphasize giving the picture unexpected details which complicate what the text says. In Gravity’s Rainbow, I had to do both at once. I learned a lot about the limits of what those techniques could do or how to extend them. They’re all very abstract and it doesn’t matter if you’re not a painter, but I learned a lot about how to hold action and how to concentrate people’s attention and when to do it.

JS: One thing that is really interesting about Gravity’s Rainbow is Pynchon’s use of abstract language. There are passages that are difficult to imagine. I am curious about how you managed to work through that kind of language, for example on page twenty-eight and twenty-nine. These images are very textured and abstract. How did his language stir and stimulate your imagination?

ZS: I think I did what everyone does when they read the book which is they try to take the words and then try to make a concrete image out of them. I just tried to nail that image down by drawing it. I was at a Pynchon conference and I was saying that one thing that happens when reading that book is you find yourself asking, “Did I actually just read that?” And all the professors there were nodding their heads like, “Yeah! I know exactly what you mean: ‘Is that what I think it is?’” I think that was the impetus of the project. I wanted to nail it down. This happened and then that happened, and it looks like this in my mind. I wanted to get as close as I could to that image that I imagined when I was reading the text.

JS: Did Pynchon ever contact you directly about the book?

ZS: It’s complicated. His official policy is that he has no response to the book. It’s clear that he doesn’t want to make it official. He’s not going to tell me not to do my project or say “I don’t approve,” but he doesn’t want to make a connection to my project either.

In New York, once in a while, people will come up to me and say, “He lives in my building, do you want me to ask him what he thinks about the project?” And of course I’m like, “Yeah, ask him!” But nothing ever comes of it.

JS: You have found a way to make your art accessible through your website and books. Can you talk a little bit about how you manage the business side of art and how you make yourself accessible to people who want to have art in their life?

ZS: The first time I was talking with the publisher about Gravity’s Rainbow, he was like, “We could do a limited edition and sell it for eighty bucks.” And I said: “No. Thirty bucks or less is what I want.” It doesn’t mean anything to me unless people can get it. Anybody can get thirty bucks together for something they really care about. When I was a kid I had a book that was fifty bucks. And all year I saved up for it because it was important to me. The books bring in way less money than simply selling a painting, but I want to offer what I wanted when I was a kid.

Most people who like art can’t afford to buy it. Like most young artists, I didn’t experience art directly but instead through pictures in books. It’s like music. Most people experience music through recordings. We had a revolution in music as a result of the recording industry. For me it was really important to get my work out there so people could see them without having to go to galleries all the time. That’s basically saying: if you don’t live in New York, then fuck you. I didn’t want to be that guy. I wanted the books to be accessible.

JS: I love that. On some level, anyone who is working their ass off in the art world wants to bring those handfuls of young artists into the inner circle and let them know that it won’t be easy but that this can be really fun and rewarding.

ZS: Yeah, those are the fun people. They make it all worthwhile. They’re the people who were no different from you or me a few years ago. That’s what it is all about.

JS: Would you like to say anything about We Did Porn to people who aren’t familiar with it?

ZS: Five years ago I started being in porn movies and after doing that for a while I decided to write a book about it. When I’m making movies, I make drawings of what’s going on. Two hundred pages of words and a hundred pages of drawings.

JS: What was the writing process like?

ZS: I was always a writer in the sense that I was always writing. There are two things. First, the thing I use in art I can also use in writing. Do the parts that you know and then weave those together. Then figure out what you don’t know.

Second, there is a different voice that I used in this non-fiction piece from the voice that I would use in fiction, because people can check what you say in a memoir against what their own reality is – you share a reality – because if you describe the weather as insane and moody every day, then they have to be able to believe the weather could be that way every day in real life.

There is a line in a Martin Amis piece where he talks about the bloodbath of the sunset, but it’s about London. That’s in fiction and so it’s okay, but in non-fiction it wouldn’t work because it would seem over-wrought and no one would believe it. I had to learn where that line was and rein it in to some degree. A lot of it was taking notes of all those things anyone would write down, those moments where you think to yourself, “I need to write that down.” So I made a book out those moments.

JS: So were you actively writing while you were making movies or did you write it after the fact?ZS: I wrote things down in a journal and took a lot of photos. At some point I realized I had a book, and then I used the photos to help fill in details.

JS: At the beginning of We Did Porn you discuss the obnoxiousness of the art world. Care to go into that a bit?

ZS: People think that there is an art world, and maybe there is, but I don’t live there.

JS: But you went to art school and have an MFA from Yale. You don’t consider that living in the art world? Do you feel like there was any sense of apprentice/teacher relationship during those years that felt like the art world?

ZS: There isn’t anyone at any of the schools who make anything remotely like what I paint. You go and get who you get. Look at Mel Bochner. It’s not like we have anything in common as artists. I went to graduate school because to become a professional artist you have to find a way to hang out with other artists until someone with more power likes you. So if you don’t sell drugs, dance, or are part of some hippy collective you need to find a way, and grad school is the most obvious and most expensive way. But I got a loan and went to the fanciest graduate school that would accept me in order to hang out with artists for two more years. It was purely a this-is-what-you-have-to-do thing.

JS: If you didn’t have a lot of influential teachers, which artists did you look at?

ZS: I liked Man Ray, William Eggleston, Robert Frank, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Joseph Cornell, Paolozzi, and George Rhoads, who makes Rube Goldberg sculptures you typically see at airports. I love those. I always try to make a painting like those. A lot of art is like a fortune cookie or a haiku. I want the length of time you look at a piece to be more like a movie – to look and to look.

JS: In the book you move out to LA. You discuss the alt-porn world but don’t talk much about LA’s art scene. Can you tell me a bit about the difference between NYC and LA art scenes?

ZS: In terms of my work it hasn’t really changed anything. I’ve been out there for five or six years. The nice thing is that I don’t ever get invited to anything because my social network in NYC was through school, and any time someone had a show we would all go. That doesn’t happen now. People in LA know each other through art school . . . I am writing for Artillery Magazine, which is the free art magazine in LA. I like LA because it’s a little more open and a little less sure of what it’s about. There are fewer rules.

It’s still the art world, but it seems like nobody knows what’s going on, and I like that. The line between high art and low art is much thinner. They’re not sure whether Mark Ryden is an artist, which is interesting coming from New York where they definitely know that he isn’t an artist. In New York it’s a business. In LA the entertainment business is the model for everything else. So people who are nobodies show up and are suddenly taken very seriously. Every other business seems to work like that model.

JS: In the book you said, “Forgive me for getting technical – this part probably won’t be funny or hot – but we are talking about my friends here.” How much of your motivation to write this book is to dismiss myths about pornography, more specifically those who make alt-porn?

ZS: Anyone can know that any other human being is a human being and that someone who isn’t like you is still a human being, at least intellectually. But you don’t do anything with that information until you feel it. I think what a lot of artists try to do is to show one kind of person to other kinds of people so that they say, “Look, this is a whole person!” I think gay people have done a great job since the ‘90s at making a gay person with stereotypically gay habits and tics feel like a whole person. This is especially true for television. People can say, “This guy is wearing white pants and a pink shirt but he’s a whole person and now I understand that.” It makes empathy easier.

The amount of apathy most people have for porn chicks is amazing. I think most people think it’s a synonym for meth addict and that is so untrue. Part of it is that I imagine myself a few years ago. What questions did I have? What did I not know? What did I wish I understood?

JS: While you said you don’t live in the art world, you actively collaborate with other artists. Can you tell me about On the Road of Knives?

ZS: It was a fun thing. Nicholas Di Genova, Shawn Cheng, and I were like, “Let’s play a game.” It’s like a kid’s game where you draw a tank and then your friend draws someone destroying that tank, except we did it online and with tons of art school education behind us. I think it’s important for artists to have less ambitious projects that are fun so that you don’t get locked into the mindset of this has to be the best thing I have ever done. That way you still have room to experiment. Some artists get to a place where they don’t have that room to experiment. It was just: “Let’s see if this works or if that works.” Again, I learned a lot doing that because I wasn’t trying to make everything into something special. So often people get to a mental space where they won’t start something unless they know they can make it perfectly.

JS: I heard that you are doing an illustrated Blood Meridian project.

ZS: I have a bunch of friends who are fans of Blood Meridian and we were going to collaborate on doing a picture for every page of that book. Each person was going to do their own take, but weirder. Shawn Chang makes wonderful active and crazily energetic figures. Jon Meijias makes a kind of neo-Posada woodblock stuff. Craig Taylor makes these fucked-up abstract paintings. Shawn McCarthy, who introduced me to the book, makes these expressionistic caricatures of peoples into monsters. And my version was going to be everyone as female. We started to work on that for a while and then we all had shows. So we were busy making art for other projects, which is great, but it’s on the back-burner right now.

JS: You seem to always have a lot going on between your career in art, film, and writing.

ZS: If I weren’t me, I think it would be really hard not to hate me. The amount of space I take up and the amount of things I think I’m good at – it’s kind of obnoxious. You know how they say women have to be twice as good to get half as far? I feel that I have to be twice as reasonable to be considered half as sane as a normal person.